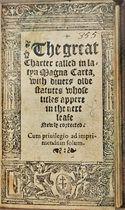

The Middle Ages

F

ormally agreed between King John of England and his rebellious barons at Runnymede in June of 1215, Magna Carta was effectively a peace treaty that aimed to reform aspects of the king’s abusive government. In addition to its famous “due process” clause (chapter 39), and its provision that justice would be done without denial or delay (chapter 40), Magna Carta guaranteed a range of property rights, and the operation of justice in part through trained officials and local courts. Also included was an enforcement clause, providing for formal judgment of the king by a committee, and the use of force, in case of a breach of terms. Though immediately renounced, the “Great Charter” was reconfirmed after John’s death in 1216, and later became both statutory law and a foundational constitutional text in the Anglo-American tradition.

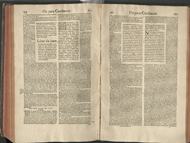

B

aldus de Ubaldis (1327-1400), one of the great medieval jurists, offered the first full scholarly and didactic commentary on a peace treaty, the Peace of Constance (1183), which was circulated with his other works and became a common teaching text in medieval law schools. The Peace of Constance was one of the most consequential medieval peace agreements in Italy. It helped to liberate the northern Italian cities from the overlordship of the Holy Roman Emperor, and led to the age of the popular, self-governing communes. In the pictured edition, the text is at center with Baldus’s surrounding gloss.