The Early Modern Period

Charles I of England (1600-1649) was denounced for domestic violations of rights – particularly rights of consent to taxation and liberty from punishment without due process – whose basis could be traced back to Magna Carta. In 1642, after a long period of simmering conflict with Parliament, Parliamentary forces opened the English Civil War against the monarch. Charles was captured in 1647, in the course of the war, and continued to seek allies until he was brought to judgment. A High Court of Justice, formed after the royal courts refused to indict Charles, found the king guilty of treasonably waging war against Parliament and the English people, and held him responsible for those killed in the Civil War. Charles rejected the court and its charges, claiming sovereign and divine immunity, but was executed in January 1649.

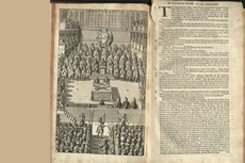

A True Copy of the Journal is an anti-Parliamentary account of the trial, published over two decades after the Stuart monarchy had been restored to the throne. The image of the courtroom, showing the defendant Charles I at trial, facing the commissioners who signed his death warrant, appears to be the first law book illustration depicting a historical trial and courtroom in detail, including identification of the key figures present. However, it commemorated for Stuart supporters the infamy of the event rather than its justice.

An Exact and Most Impartial Accompt appeared after the Stuart-led trials of commissioners who had convicted Charles I. The government of Charles II, Charles I’s son, sought out and put on trial those who signed the death warrant of Charles I and various other officials and associates of the court. Of the 59 who signed the warrant, 31 were still alive in 1660. Those who did not flee abroad were executed or imprisoned for life.

The royalist work argues, among other things, that the House of Lords had rejected the treason charges against Charles I, that the Lords and the monarchy were abolished (unjustly) after the verdict, and that Parliament had mercilessly declared that all sons of Charles should die.

The opened pages show witness testimony from the trial of John Carew, who was executed.

Gentili (1552-1608) is rightly considered a founder of early modern international law, an academic tradition founded on medieval Roman and canon law. Gentili’s De jure belli libri tres [Three Books on the Law of War] (1589) was the most comprehensive legal treatise on the subject to his time and a main influence on Grotius (though without the latter’s admission). Gentili did not offer guidelines for post-bellum justice, but reviewed some common principles. In the De jure, written while Gentili was teaching at Oxford, he affirmed that captives should not be slain unless they resisted (Bk. 2, ch. 16); and that whoever violated this principle could be punished. Soldiers who simply surrendered were likewise normally protected (Bk. 2, ch. 17). Gentili also observed that those who deeply offended against the laws of war could face punishment including death at the hands of their opponent (Bk. 2, ch. 18).

The Treaties of Nijmegen (1678-79) ended the Dutch Wars (1672-78) and brought more than a half-dozen European powers to terms, including France, the Dutch Republic, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire. In a period of highly developed diplomacy, but without effective tribunals to redress wrongs within the Westphalian system, the Dutch Wars saw figures like Louis XIV use war as a means of territorial acquisition. Typical for the period, the treaties contain articles on the gain and loss of territory, post-war restitution of rights, removal of troops, and the good faith exchange of hostages.

The most celebrated figure in early modern international law, Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) was a Dutch scholar, polymath, jurist and controversialist. In De jure belli ac pacis [On the Law of War and Peace] (1625), Grotius laid out a strong conception of the sovereign state, based on the nature of government and its natural rights. Grotius noted that punishment in war should aim at some good, including future prevention and the reformation of offenders (Bk. 2, ch. 20). He counseled moderation for just victors (Bk. 2, chs. 20-25), and offered detailed ideas on liability to punishment for crime (Bk. 2, ch. 21). For Grotius, those who command a wicked act, consent to it, advise or encourage it – even those who do not aid those harmed when given authority to do so, and those who do not disclose crimes when they are obliged to – are liable to punishment. These precepts were applicable in contexts of war, though Grotius did not discuss how they should be carried out. Turning to those who suffered in conflict, he approved rights for refugees who innocently sought asylum. Grotius’s ideas more broadly, particularly on rights within and beyond conflict, would have a wide influence on European moral thought in the next two centuries.