Early English Legal Education

Medieval English legal education began in practice. The king’s courts predated any formal law school: legal education was had in court, and through the discussion of cases and law. Students studied writs, the foundation of legal procedure, and probably had at hand brief reports of early cases. The Inns of Court in London, where students heard lectures and debated hypothetical cases, developed in the fourteenth century. There students were exposed to a rather more formal training, and enjoyed the camaraderie of members of a developing profession. Early literature, at first in manuscript form, focused broadly on procedure, cases, and statutes. By the seventeenth century, study aids specifically aimed at students also became available.

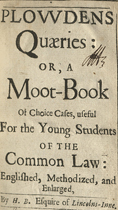

Edmund Plowden, Plowden's Quaeries: or, A Moot-Book of Choice Cases (London, 1662).

Beyond the courts themselves, “moots” were the most lively way to learn and debate points of law. Although not at first strictly descriptive of a single exercise, they involved “pro” and “contra” discussions of a hypothetical case, often involving complex fact patterns raising subtle points of law. This volume includes both thorny hypos and arguments for either side in order to provide “weapons” for students’ “particular advantage.”

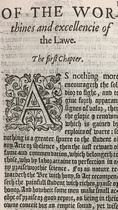

William Fulbecke, A Direction or Preparative to the Study of the Law (London, 1620).

Fulbecke’s treatise was the first devoted to instructions for prospective students of English law. The worldly barrister advised on the qualities necessary for success (studiousness, sobriety, even a good diet), and good preparatory reading (the classics). He also included an introductory discussion of property and a glossary of Latin legal terms. First printed in 1600, the work was reprinted into the eighteenth century.

Thomas Littleton, Lytylton Tenures Neulye Imprynted (London, 1545).

Thomas Littleton (d. 1481) penned the first treatise on English property law. His Tenures was frequently republished from the beginning of legal printing in London (ca. 1481). Together with Edward Coke’s later commentary on it, “Littleton” was the student’s essential guide to property for nearly three centuries. Produced in small formats, the book was a portable reference guide in the classroom and courtroom. This copy’s annotations add rich historical interest.

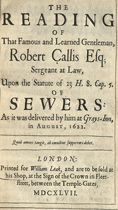

Robert Callis, The Reading of That Famous and Learned Gentleman, Robert Callis Esq. Serjeant at Law, Upon the Statute of 23 H. 8. Cap. 5. of Sewers: as It Was Delivered by Him at Grays-Inn, in August, 1622 (London, 1647).

The readings held in the Inns of Court were lectures on statutes by an invited expert, here the barrister Robert Callis. His discussion of Henry VIII’s statutory law on sewers was not really about urban waste removal. He discussed water law and property rights; and public and private obligations connected to them in a broad scope, including complex hypotheticals for classroom discussion with his own solutions.

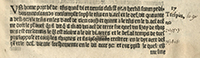

De Termino Michaelis. Anno. VI. Edwardi Quarti [6 Edward IV (1466)] (London, 1557).

Early case reports were gathered in small volumes known as Year Books. Typically brief, the cases date from 1268 to 1535. Like much of early English law, they are in Law French, a specialized language used in court until the seventeenth century. The page shows an excerpt from The Case of Thorns (1466), still mentioned in some torts classes today. An important but misprinted word (muto) from the case has been struck through and corrected (invito), perhaps by an astute student. The case depends on the fact that the thorns fell on the plaintiff's property "without [the defendant's] will" (ipso invito). By 1572, Tottell and his workshop had corrected the error. It may have annoyed practitioners, but was a good test for law students.